Photo credit: Amy Dykens

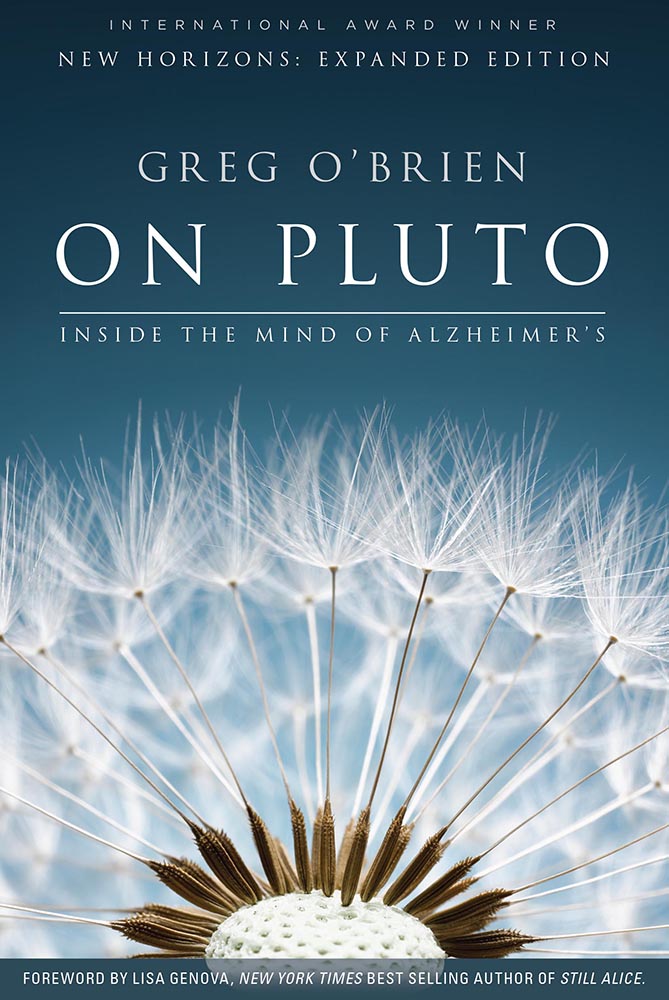

A career journalist, Greg O’Brien’s latest book, an international award winner, “On Pluto: Inside the Mind of Alzheimer’s” is the first book written by an investigative reporter embedded inside the mind of Alzheimer’s, chronicling the progression of his own disease. Lisa Genova, author of the best-selling Alzheimer’s novel, Still Alice, whose screen version won an Academy Award, wrote the foreword. “If you’re trying to understand what it feels like to live with Alzheimer’s…then you need to read this book,” she observed.

On Pluto has won the Beverly Hills International Book Award for Medicine, the International Book Award for Health, was an Eric Hoffer International Book Award finalist, as well as a finalist for USA Best Book Awards. It has been translated into Mandarin for distribution in China, into Italian for distribution in Italy, and a foreign edition is distributed in India.

O’Brien was diagnosed several years ago with Alzheimer’s after a series of brain scans and clinical tests, and after serious head traumas that doctors say unmasked a disease in the making. Alzheimer’s—a disease that can take 20-to-25 years to run its serpentine course—took O’Brien’s maternal grandfather, his mother, and his paternal uncle, and before his father’s death, he, too, was diagnosed with dementia. O’Brien, who carries the Alzheimer’s marker gene APOE-4, is the subject of the short film, “A Place Called Pluto,” directed by award-winning filmmaker Steve James, online at livingwithalz.org. NPR’s “All Things Considered” has run a series of pieces about O’Brien’s journey, online at npr.org/series/389781574/inside-alzheimers, and PBS/NOVA took a trip to Pluto in its groundbreaking Alzheimer’s documentary, Can Alzheimer’s Be Stopped, (https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/can-alzheimers-be-stopped/).

He also is co-host with New York Times Best-Selling author David Shenk of the podcast, “The Forgetting,” produced and distributed by WGBH-TV in Boston and NPR (https://www.npr.org/podcasts/690359048/the-forgetting). The podcast is starting its second season.

O’Brien, who has spoken nationally and internationally on Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, serves on the Board of Directors of the distinguish UsAgainstAlzheimer’s in Washington, DC, is an advocate for the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund of Boston, and has served on the national Alzheimer’s Association Advisory Group for Early Onset Alzheimer’s. Over his career, O’Brien has written for national and regional media, among them: Huffington Post, Psychology Today, Boston Herald, Boston Magazine, Boston Metro, New York Metro, Philadelphia Metro, Time, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, USA Today, Providence Journal, Cape Cod Times, Boston Irish Reporter, Runner’s World, Reader’s Digest, Associated Press, has consulted on PBS/NOVA scripts, and others.

In addition, O’Brien was a founding managing partner of Community Newspaper Company, created by Fidelity Investments in 1991. Community Newspaper Company, one of the largest newspaper companies in New England, was then sold to the Boston Herald, then GateHouse Media, which recently acquired Gannett, publisher of USA Today and scores of other newspaper and media. The expanded GateHouse Media company now operates a combined 260 daily newspaper operations, along with community weekly newspapers, more than any U.S. news publisher. In addition, O’Brien was editor & publisher of Cape Cod Publishing Company, a group of seven community newspapers that were part of Community Newspaper Company.

He lives in Brewster on Outer Cape Cod where he and his wife of 42 years, Mary Catherine, raised their three children: Brendan, Colleen and Conor.

Visit Greg’s blog, On Pluto: Reflections From Beyond

Reflections from the family

Excerpts from On Pluto

“Miles from Nowhere”

Twenty-seven hundred and fifteen miles is a long way from home, particularly when you grow up on a rustic 1,120-acre ranch about 20 miles outside Phoenix in the 1950s, as far flung from Boston as the north rim of the Grand Canyon.Moving to Boston with my world-beating journalist husband in 1979 after his tenure as an investigative reporter at the Arizona Republic, covering white-collar crime, the Mexican Mafia, and the Aryan Brotherhood, I clearly discerned we were on new ground. It snows here, is biting cold in winter, and rains often; spring is a day in early June, and summer is the bliss of all. But don’t hold your breath. Early on, Greg lived in my world; now I live in his, and it’s getting far more complicated now.When I moved East, somewhat guardedly with Greg, paying homage to marriage vows, I was entering the forbidden city, land far east of the Mississippi—the dividing line, my rancher father had taught me, between “real people” and the Eastern Establishment. If you haven’t guessed, my husband and I were born on different planets. He grew up in Rye, Westchester County, a short train ride from Manhattan. We have always agreed on child rearing, faith, hope, and charity, but when it came to geography, we are the inverse of simpatico.

Just sayin’, as my husband likes to quote.

I dream of returning one day to Phoenix, to my family, six supportive, loving brothers and sisters, their children, and extended family, in the valley of paradise—particularly now as my husband, of 40 years of marriage, declines in Alzheimer’s, a black hole now slowly sucking him in, often beyond the notice of others. Yet Phoenix is not in the cards for the moment. Likely, I will not return until my husband is in a nursing home, or writing in Heaven for the Daily Amen! The life of a caregiver is fraught with the unknown. For better or for worse…

What’s a nice girl like me doing in a place like this?

Like the probing Cat Stevens song of 1970, I feel, as a caregiver in the throes of Alzheimer’s, that I’m “Miles from Nowhere.” Some tea for the tillerman might be nice. The family tiller has now been handed to me, and there’s no land in sight.

The rugged White Tank mountains, 20 miles northwest of Phoenix, frame Litchfield Park like a Frederic Remington painting. Litchfield Park is an anchor to the McGeorge family. In 1923, Col. Dale Bumstead, a World War I hero, and his wife, Eva, purchased about 1,100 acres of failing citrus gardens and date groves just outside Litchfield Park with a vision for a ranch of international renown. Col. Bumstead named the ranch Tal-Wi-Wi, Hopi Native American that translates to: “Where the sun first shines upon the fertile earth.” In time, the name would have new meaning for me.

Visionary Col. Bumstead didn’t have much to work with from the start. Yet fast forward to 1946 when he hired my father, Ken, another war hero, a Lt. Colonel who served in World War II under Gen. George Patton. It was Dad’s first job out of the Army, employed on the recommendation of his father, William, a close friend of Col. Bumstead, and at the time a noted agricultural chemist at the University of Arizona Agricultural Chemistry and Soils Department. My dad had no previous farming experience, but Col. Bumstead wanted a hard-working war veteran who wanted to get his hands dirty. And he got one!

And so I was raised on magnificent Tal-Wi-Wi, with my devoted mother, Mary Ellen, a saint of a woman, and six siblings: Martha, Tommy, Louie, Barbara Ann, Nancy, and Robert. I was fourth in line in this magical oasis in the middle of the desert that defines Phoenix. We were surrounded by vineyards and sweet orchards of oranges, grapefruits, and tangerines, where we could pick our lunch before school. The entrance to the ranch welcomed with giant date palms and beautiful eucalyptus trees that lined the perimeter. We had rose gardens and gardens filled with snapdragons, gardenias, camellias, and every other variety of flower that could greet the dry Arizona sunshine.

Tal-Wi-Wi, over time, attracted worldwide attention for its incredible fruit, prize-winning Hereford cattle, dates, and grapevines, including the first commercial production in the world of the prized cardinal grape, a transcendent cross between the flame seedless and ribier table grapes. The New York markets were agog. Little did I realize as a young upright girl on a farm in rural Arizona that my future one day would be Back East, Miles from Nowhere.

As Tal-Wi-Wi grew in stature, it attracted notoriety around the world, among them, many years ago, the Crown Prince of Arabia, his royal highness Saud Al Saud, and on December 2, 1949, the Shah of Iran, a young, handsome 30-year-old Mohammed Reza Pahlevi, a Middle East strongman who in 1967 took the title of Shāhanshāh (“Emperor” or “King of Kings”) and was overthrown by the Islamic Revolution of 1979. At Tal-Wi-Wi that day, the Shah was sovereign. He had come here at the invitation of President Harry Truman to witness the miracle of transforming arid desert to productive land through irrigation. Truman, a Missouri boy from Independence, had known my grandmother, Catherine McGee Soden from Kansas City; they were friends. Family lore has it that after Truman recognized the State of Israel in 1948, my grandmother, a devoted Irish Catholic, congratulated him, having recently visited Israel herself, proclaiming, “Mr. President, they think you’re Jesus Christ over there!”

“Now, Catherine,” Truman is said to have invoked, “You know they don’t believe in a divine Jesus!”

The Shah that day on Tal-Wi-Wi was feted with Arabian dishes, as well as elk venison, wild turkey, and antelope broiled over an open fire. Col. Bumstead, we’re told, had bagged the game in a hunting trip. It was a feast fit for a king. My pretty sister, Martha, three years old at the time, was on hand for the occasion. Reported a local periodical, “When she (Martha) presented a large rose to the Shah, she was lifted into his arms for a big hug by the world’s most eligible bachelor.”

Did I tell you that my husband and I are from different planets?

Like many mixed marriages, Greg and I have hit for the cycle: first attraction, then marriage, children, and yes, along the way, plenty of private intimacy. Given that I studied journalism at the University of Arizona, I was attracted to Greg because he was a writer, and a good one; he was also good-looking. He isn’t particularly romantic, but he is smart and easy on the eyes. The two seemed to go together for me. There’s nothing romantic about living with a journalist; there have been times I wished I had listened to my mother.

She once asked me at the start of the relationship, “What does Greg do for a living?”

“He’s a writer,” I said.

“I know,” my mother replied in great wisdom, coming from some family wealth, “but how does he make his money?”

Still, the two of us made for loving parents. But as the kids grew, and took up lives of their own, we began to drift, just as Greg’s parents had years earlier. It was obvious to the children. It was no one’s fault. Over time, there were the predictable hostile exchanges of marriage, penetrating moments of silence, perhaps even thoughts of separation, as we tried to discern the new “us,” life after parenting. The intimacy was gone; Greg often slept on the couch. Alone in our bed, I often dreamt of Tal-Wi-Wi.

Years ago, it got worse as Greg’s mother drifted deeper into Alzheimer’s, and we became family caregivers. I saw firsthand the terrifying, disconnected, debilitating, hostile nature of this disease. Then to my horror, I began to see it in my husband; Invasion of the Body Snatchers, as Greg calls Alzheimer’s, slow at first, then a quickening pace. The explosions, the rage, the drifting, the ceaseless short-term memory loss, absence of filter and judgment, absence of balance at times, repeating himself, asking the same damn questions. I was out of my mind. I was in denial, thinking he was just becoming more of a perfect asshole; Greg has always sought perfection. In time, the evidence was overwhelming, particularly after Greg’s parents had died, and he was no longer consumed with caring for them. He was privately consumed then with fighting his own demons.

Yet before Greg’s parents’ death, I began noticing a change in them, a softening in their relationship. More and more, they depended on one another. They were both fighting off progressing dementia, and Greg’s dad in addition had cancer and circulation disease that ultimately placed him in a wheelchair. More and more, they became one, completing a life circle. It was stunning to watch. They needed each other again. Alzheimer’s had begun healing their marriage.

British novelist E.M. Forster once wrote, “You must be willing to let go of the life we have planned, so as to have the life that is waiting for us.”

The life waiting for me is more and more a nightmare. I didn’t sign up for this. When we received Greg’s diagnosis at his neurologist’s office, after a battery of tests, brains scans, and a gene test, I had very little information about Alzheimer’s except through the experience with his parents, which was mostly destructive. Greg’s mom, for example, was particularly nasty and made derogatory remarks to him, her main family caregiver. I didn’t know at the time that this is part of the disease. Now it’s my turn, and I am the receiver of that unbearable behavior. At least I can TRY to shove it off to Alzheimer’s, but it is never easy. I had no sense of where to turn for help, support, or even how to express the diagnosis with family, friends, or co-workers. I was lost, and crept further inward. There is no single handbook one can read to prepare; each journey is different, each course of the disease takes different, meandering turns—no two are alike, the experts will tell you, an observation that is clearly numbing in so many ways, as best-selling authors and close friends of ours, David Shenk and Meryl Comer, write in their respective books, The Forgetting and Slow Dancing with a Stranger. Must-reads!

My family in Phoenix was first to respond. My loving siblings, who have known Greg since his 20s, were supportive and reached out to me in ways that told me I wasn’t alone. Still, they were close to 3,000 miles away. Greg’s siblings, in contrast, while far closer in geography, were generally more restrained in outreach. Understandably, denial is a survival instinct when a disease cruises through a family. As Henry David Thoreau calls Cape Cod the “bare and bended” arm of Massachusetts, I felt bare and bended.

It wasn’t until legendary filmmaker Steve James (Hoop Dreams, Life Itself, and other award-winning films) produced a short documentary about our family’s journey, A Place Called Pluto, part of Cure Alzheimer’s Fund initiative, Living With Alzheimer’s—documenting the various stages of Alzheimer’s (livingwithalz.org)—that word got out. The film played at notable film festivals across the country, including Tribeca in New York, Washington, D.C., out West, and a preview at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in midtown Manhattan.

But still, I wasn’t ready to deal fully with it, having just come off the cliff of Greg’s mother. I was in denial, didn’t want help, and was not emotionally prepared for it, in spite of numerous supportive outreaches from close friends on the Cape and Boston. Caring friends Leslie and Paul Durgin in Milton outside Boston hosted an unsung heroes cookout at their home, in support for two close women with breast cancer, Becky Smith and Nancy Souder from Cape Cod, and for me, the caregiver. It was awkward in its own way, but healing. Thank you, Durgins!

However, it wasn’t until a Boston television show, WCBV-TV’s Chronicle, produced with host Anthony Everett, did an incredible half-hour segment on our family—one that won an Emmy and a National Headliner First Place Award—that the story hit hard at home. I, for one, watch Chronicle every night, the best news magazine in the nation. I’m a big fan, but I never imagined the wide viewing it would get in my small little world on Cape Cod. Host Everett’s father, I learned later, died of Alzheimer’s. The segment, I’m told, had hundreds of thousands of hits on Chronicle’s website. When I arrived the following morning at my teaching assistant job at Nauset Regional Middle School in Orleans, I was greeted with scores of tearful hugs, encouragement, flowers, and generous offers from our three caring guidance counselors that “their door is always open.” Oh well, thanks to Chronicle and Anthony Everett, everyone on Cape Cod knew, and I needed now to accept the disease as well.

Months later, after having read Ptolemy Tompkins and Tyler Beddoes’s inspiring book, Proof of Angels, an angel came knocking at the door in the form of Frank Connell, a local painter and a saint of a man. I had asked him for an estimate to repaint a master bedroom with a high cathedral ceiling, a master bathroom, a stairwell, and hallway— work expected to cost thousands of dollars by today’s standards.

Connell inspected the areas then asked, “When do you want me to start? I didn’t know whose house this was until I drove up.” Frank had just buried his mother after her bout with Alzheimer’s, and had seen the Chronicle piece.

“Frank, I can’t go forward until I have an estimate,” I said, knowing our bank account was draining toward empty.

“Oh,” Frank interrupted. “There’s no charge for this. I’m doing it for free!”

I started crying. “No, you can’t do that,” I said.

Frank hugged me and replied, “This isn’t something you need to cry about. You have plenty of crying ahead of you. It’s your turn to be taken care of…”

I kept crying; my husband did as well when I told him later of the exchange.

Weeks later, when Greg and I were speaking in Phoenix and Tucson before the Literary Society of the Southwest, Frank and his crew of six performed a miracle. Proof of angels. There were more angels to come. To mention a few: our chimney sweep, Judd Berg, an old friend of Greg’s, cleaned the wood stove chimney in the family room; landscaper Lindsay Strode cut the lawn when Greg’s sitdown broke and he couldn’t afford to fix it; childhood friend Mark Mathison replaced rotted siding; neighbor Charlie Sumner, retired “Mayor” of Brewster, loans Greg every home tool imaginable, then shows him how to use it; close friend Brewster Police Chief Dick Koch, a guardian angel in so many ways, along with Paul and Leslie Durgin of Milton; mentor Peter Polhemus, who guides Greg financially and tries to laugh at his sick jokes; and Boston attorney John Twohig, a surrogate brother to Greg, put us up on Nantucket for a long weekend getaway at the elegant White Elephant on Nantucket Harbor, and paid for our fine meal. And there were scores of other acts of kindness from organizations, noted in the Epilogue, like the Washington, D.C.-based UsAgainstAlzheimer’s (UsAgainstAlzheimers.org), the Chicago based Alzheimer’s Association (alz.org) and the association’s Massachusetts/New Hampshire branch, the Boston-based Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (curealz.org), the Cape Cod-based Hope Health: Hope Dementia & Alzheimer’s Services (hopehealthco.org), and the Brewster-based Alzheimer’s Family Support Center of Cape Cod (alzheimerscapecod.com), run by our close friends Molly Purdue and Melanie Braverman. Molly talks about our family’s journey in “The Nun Story” in this On Pluto expanded edition.

Today, I read a lot of Christian author C. S. Lewis. He also speaks to my heart. “It’s not the load you carry that breaks you,” Lewis writes, “it’s the way you carry the load.”

I first needed to learn how to carry the load, then I needed to learn that I was being carried. The heavy lifting took me back to scripture. A verse in Matthew 11:29-30 has new meaning for me. Jesus said, “Take my yoke upon you…for my yoke is easy to bear, and the burden I give you light…”

Light shines in all ways. One of the blessings and challenges of this journey with Greg is that through persevering, courageous, hard work he has attained national and international respect as a person living with Alzheimer’s. At first, I felt left behind. Greg was getting the well-deserved attention, and I was cleaning up the mess, particularly difficult with his loss of continence at times.

“How’s Greg doing?” I’m asked all the time.

I have to admit that at times it’s personally distressing, the “drivebys,” as Greg calls them. But what about me, and what about all the other caregivers, who selflessly care for their loved ones, many of them in stages of dementia now deeper than my husband’s? We deal with symptoms, we deal with terrible depression, our immune systems are breaking down. We are on the edge! How about us?

Greg is a cartoon guy and also loves watching black-and-white reruns of The Three Stooges. There’s a Bugs Bunny cartoon that Greg loves where Bugs pipes up, “How about me, boss? How about me?”

Well, how about me, boss, and how about all the other caregivers?

I do think the focus is changing, collectively a better understanding as noted above, that when one person has Alzheimer’s, the entire family gets it. I was shocked at a recent international Alzheimer’s conference in Lausanne, Switzerland, when host George Vradenburg, head of UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, asked me after Greg’s speech: “I want to know how Mary Catherine feels?” Wow! So I told them of the paralyzing isolation, anger, and fear. Those in Alzheimer’s are alone; so are the caregivers, as if one of Pluto’s moons, perhaps Charon, the largest and locked into the ebb and flow of Pluto that the two in some scientific circles are considered a “double dwarf planet.” My husband and I fear the same things in parallel emotions, searching for ways to vent. Like Greg, I cry, yell, feel numb in the head. Often we collide in our orbits.

The same happened at an Alzheimer’s Association conference in Tucson, Arizona. It brought me to tears as I sat on a stage in front of about 500 people. I’m not a person who wears my heart on my sleeve, so this was difficult, but it was also very moving. People care….

“So, what are you going to do?” I’m asked all the time. This question is the most exasperating. How can I know what I am going to do when I don’t know what the changes next week will bring? As one caregiver, a friend of mine said, “I lose a little bit of him every day.”

If finances weren’t a huge, distracting concern for us, this question could glean more answers. Greg, who can’t make the money he once earned, has gone through all of his retirement funds, not that there was much to begin with, and with both of us from large families, there is no inheritance, other than some walking-around money. We face bankruptcy in years to come. So when your financial future has no future, the answer to the question “what are you going to do?” can be a walk off the plank. Yet angels abound, and this gets back to accepting the life I had not anticipated. Or as my husband likes to joke, “We got plenty of money; it’s just tied up in debt!”

Let me vent a bit, if that’s okay with you. I am a checklist lady— by the day, the month, the year. I love crossing all those “have done” off my list! With Alzheimer’s, my checklist never ends, and never gets checked off. Frustration for a checklist lady. Enter more faith in striving to accept the unknown. Back to the marriage vows: “For better or for worse…til death do us part.”

I’m heading into the worst part now. We are going on 40 years of marriage and memories together, but they are slowly fading for Greg. I’ve spent 40 years of my 60-plus years of life with someone who won’t remember that we honeymooned in Hawaii or met in college, or traveled to Ireland. I will be left alone with those memories as I grow old. That is scary and sad for any caregiver. Sure, there are memories that I want him to forget; we’ve discussed that, so I have to be grateful to some extent! But to grow old and not share the more significant part of your life is more than disconcerting. I ask more and more “do you remember” questions, and he doesn’t. It gets increasingly sad. The anger, now with both of us, escalates.

Kindness with Alzheimer’s can go out the door. You have to become comfortable with a less-than-perfect relationship. Greg exudes kindness and softness and humor when he’s outside the house, an effort that saps him. At home, he lets his guard down and is easily angered. For example, he gives me a list of what he wants me to get at the store for him. I come home with his three boxes of frozen fruit bars, Cracker Barrel cheddar cheese, salad, Bumble Bee tuna (he’s addicted to that), but I forgot the chunky peanut butter. Not good— he is pissed and angry. The perfect asshole. Did I tell you about that?

When I forget something he screams, “WE talked about this!” But I have to listen to things over and over and over. Greg yells not just at me, but to his poor Mac laptop, but I believe the Mac is more resilient than I am. If only I could just be a technology source and not feel so embattled.

Technology has become Greg’s friend now—his laptop, his iPhone, and last Christmas I gave him Google Home, a calming device that can help in his frustrations when he’s writing and can’t remember a word or what it means, or when he yells at me: “I don’t understand; I’m confused.”

“Okay, Google,” you ask a white cone-shaped cylinder, and Google responds.

You heard he threw a shoe at me at the airport, absorbing confusion and rage. He feels badly about that. I made sure of it. In jest and in repentance, he asked Google Home recently if it was okay to throw a shoe at your wife. “That’s not normal human behavior!” Google replied. Google is now my new best friend.

Then there’s the time recently when he misplaced his phone for the 40th time that day. He’s yelling and screaming at me and Conor, though I understand he’s upset about losing memory. I worry sometimes in his anger that he will hurt himself. Conor in the moment told Greg to check in the car, that he would call the cell phone. In the car by himself, Greg could hear the phone ringing, but could not discern where the sound was coming from. His brain couldn’t pinpoint; the ringing, the noise to him appeared throughout the car, on the floor, in the front seat, in the back seat…

Like a blind man, he told me later, Greg began checking for phone vibrations. Finally, he found the lost phone. You’d think he’d be happy. He was in such rage about losing his phone so many times that day that literally he had to hurt something. So he grabbed a coffee cup on the floor of the car, a souvenir of a memorable weekend trip to Manhattan with our daughter, Colleen. It had become my favorite, a Starbucks New York City cup with a yellow cab imprint. In rank anger, Greg hurled it against a nearby stone wall, a perfect strike fast ball with his left hand, though he’s right-handed. I was in the front yard at the time. Greg looked up to the sky and yelled expletives. “If you want me, you can take me now,” he yelled to Alzheimer’s, then walked by me, slamming the door behind me. Seconds later, he sensed what had happened and opened the door. I was outside crying, and walked in. I hugged him, saying, “I know it’s not you, it’s the disease.”

Greg then told me that he’d be right back. He went outside again, looking up to the sky, spewing expletives again. “You can’t have me today, Alzheimer’s,” he told me he screamed.

Ironically, Alzheimer’s now is starting to heal our marriage, as it did with Greg’s parents, drawing us closer together, letting go of the past, holding on to the future.

I find myself relating more today to caregivers fighting the disease. They seem more real to me than others. There are no “drive-bys” with this group. One woman I’ve come to know and love is Margaret Rice Moir, a beautiful writer whose husband Rob is struggling with Alzheimer’s, as Greg noted earlier. They live just a few blocks away from us. I find peace and strength in Margaret’s writing about this disease.

“Many of us know the evolution of Alzheimer’s,” she writes. “We know the bone-chilling fear when you wake up in the middle of the night, worrying about what’s to come, the financial hurdles, the shifting roles. Life surely changes after a diagnosis. It does for the patient. It does for the caregiver. Love becomes more complicated, intimacy more challenging, patience more ephemeral…We know the time we have now is precious. The good and the bad, it’s all we have. So, lover, mother, nursemaid, nag, we caregivers are lost somewhere, floating in and out among our many, often conflicting, roles…While love can be ever so much more challenging in these times, it can also be richer, deeper, and more mature. And in our best moments, there is joy in that. Touch becomes the language between us.”

As I often lay awake at night when sleep is robbed, I reflect back to the serene, innocent days on Tal-Wi-Wi when life and promise were ahead of me. The land “where the sun first shines upon the fertile earth” still embraces me. I used to watch in awe as the sun rose above the resplendent Arizona mountains. Now I watch the sun rise at first light over bountiful Nauset Beach and brilliant sunsets on Cape Cod Bay. Observing this inspiring earthy phenomenon has always been a soul-searching encounter for me. But “sundowning” now takes on a new meaning. As the sun sets and the light goes dim, Greg’s confusion increases, his mood worsens, and his patience and reasoning ebb, generally followed by language unacceptable in polite circles.

I cringe. A favorite time of day is now a worst fear. Yet my friend Margaret is correct when she writes, “It’s no one’s fault. It’s just the disease. Once my husband saved me; today I’m saving him.”

Miles from nowhere…

(Postscript: A journalism major years ago at the University of Arizona, I wrote this with some assistance from my editor husband, Greg. It took many months to dig deep. The words are from my heart, my feelings, my soul, for better or for worse. We complete each other’s sentences today…)

The Good and the Bad

Conor Michael O’Brien

Those with Alzheimer’s are not the only ones who forget. We all forget. And more than not, we all want to forget. When I was a baby, I had a bad bout with colic, my dad told me. He fought colic himself as an infant. Twenty-seven years ago, he wrote an expressive piece in Boston Magazine about it. Looking back, he calls the piece humorous.

I read it for the first time recently, and was immediately devastated, thinking of what he and my mother must have gone through day and night with a constant ringing in their ears from my deafening cries. I was in tears reading the piece, imagining my dad, almost three decades ago, trying to get through the work day with my ear-splitting screams screwing up his routine. The column, of course, was well-written—a similar style of writing he has today, and thank God he hasn’t lost a step in that regard, though he struggles desperately in so many other areas. I’ve now apologized with a sarcastic smile on my face for the terror that my newbornself caused them, then realized that that short chapter in Dad’s life was a cakewalk compared to his challenging walk today. Witnessing firsthand his gut-will to fight against the weighty burden he carries is inspiring.

As Dad notes in his Boston Magazine piece, I fussed, actually cried, many hours a day, as millions of colicky babies do, a common phenomenon. My pediatrician, according to the column, told my parents at the time that infants “are nothing more than potatoes with a bunch of unconnected nerves.”

Apparently, the colic got to the point where one day in his upstairs office in The Cape Codder newsroom, my dad heard a baby crying in the lobby. He panicked. “Oh, my God,” he wrote in the piece. “Conor has tracked me down. He knows where I work!”

So Dad reached for the phone, calling a Boston Magazine editor, asking if he could write a column about colic, and interview one of the world’s top baby experts, Dr. T. Berry Brazelton, the “Dr. Spock of the 80s,” as Dad calls him. Dr. Brazelton, in an interview, reassured my father that colic was normal, that he and my mom should stop “fussing over it,” that follow-up studies on colicky babies indicate that they “grow up to be extremely intelligent, alert children.”

I feel good about that, and about my relationship with my dad today. We have much in common—physically, emotionally, and in how we often think. In some ways, we are a carbon copy of one another, and I am proud of that. Over the years, my dad has sacrificed, as all good fathers, to care for me, my brother, Brendan, and my sister, Colleen. He never ceases to amaze me in all facets of his life, trying to focus on whatever task is at hand and always delivering on it— even with a screaming newborn in the background. That’s impressive enough at the prime of life; now what he’s able to accomplish in his battle with Alzheimer’s is truly astonishing.

A few years ago, when Dad told us about his diagnosis, we all feared the worst, but deep inside we all knew that he was going to put up a fight and rise above the disease as best he could. We were a close family before; we would be even closer now. So I signed up for duty. As it is with the New England Patriots and Coach Belichick when someone is down, “Next Man Up!” After Dad had cared for me all these years, the mantle had been passed, and I was to care for him now. I became his day-to-day associate, the family caregiver who assists with his work, does much of his research, helps in editing, participates at times in speeches and interviews, drives and travels with him, and finds his phone, laptop, and car keys scores of times a day when he loses them. My job, as we joke, is to try to make sure Dad “doesn’t lose his shit.”

My dad and I have grown through the process, learned more about each other, have become much closer. Looking back, I realize this is a blessing—on the road with Dad, across the country and parts of the world, in interviews with NPR, PBS/NOVA, Fox News, and scores of newspaper, radio, and television stations, in speeches to groups as large as a thousand, and as intimate as a gathering at a nursing home. There are a lot of ups and downs now. Dad’s bad episodes now outweigh the good ones, but I cherish each time I see that he’s having a good day for whatever reason. A smile goes a long way.

Dad could always light up a room with his smile, charm, humor, and presence; still does. It’s muscle memory for him. He can captivate a room in an instant with his charisma, and simply his words. He can draw in an audience at the drop of a hat. Bad days now for him are as common as the sun rising in the morning. His ability to adjust, put a smile on, and strive on is as courageous as it gets.

But there has been a steep learning curve for both of us, so many twists and turns. There was a time not long ago when Dad and I were in Washington, D.C. for an UsAgainstAlzheimer’s annual summit; Dad was speaking at the Capitol Hill event. The day before the speech I worked out in a fitness center at the downtown hotel where we were staying. Dad remained in the room, saying he was feeling a bit foggy. He wanted to rest. When I returned about an hour and a half later, he was on Pluto. He didn’t know where he was, and in the moment, who I was. Freaked me out. I’ve witnessed these trips to Pluto before, but this one was more intense. It could have been a minor stroke, Dad was told later, a “TIA,” a transient ischemic attack, as doctors call them, common in Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementias. I had to look this up. A TIA, the experts say, starts as a brain stroke, but then lessens, leaving no noticeable symptoms or additional damage, other than a warning sign that the person is at risk for more serious and debilitating strokes. Upon Dad’s return from Pluto we spoke about it; he said it had happened before. He didn’t want to talk much about it.

More recently, I experienced yet another out-of-body Dad encounter—this one far more vocal, along the line of scores of Alzheimer’s outbursts I have witnessed. My parents had been asked to speak at a special Alzheimer’s panel at WGBH-TV in Boston. The forum was held after a special screening of the powerful PBS Alzheimer’s documentary, Every Minute Counts. Traveling to the television station with my parents in a cab from our Boston hotel, Dad had another outrageous disconnect. This one was likely caused by paranoia from this disease. We were on track, on time, for the event. I was charting the course on my iPhone. The cabbie, though, took a wrong turn close to the station. Dad instantly was uncontrollable, yelling and loudly cursing in ways that would shave the hairs off a nun’s neck. We couldn’t control him. The paranoia of dementia was in full force. The cabbie, Dad thought, was intentionally trying to deceive him, or perhaps even take him prisoner. It was as if some alien force had taken control of him. With a few quick right turns, we were back on track. After multiple apologies to the cabbie from my mother and me, we got out of the car. Dad was still in such rage that he stormed across a busy Boston street toward the station, not caring if he was hit by a car. Angels must have sheltered him.

Once inside the station, Dad calmed down after a few minutes. An hour later, he was an all-star on the panel before an audience of several hundred. No one knew what had transpired earlier, until he turned to my mom after being asked a question about the rage of the disease. He reached for her hand, told he loved her, and started to cry. It was pretty moving.

Months later, Dad had a similar explosion in Manhattan with another cabbie on our way to stay at the Broadway Plaza Hotel, the day before an Alzheimer’s podcast recording with author David Shenk at Argot Studios on West 26th Street. The cab driver, who spoke broken English, was having great difficulty maneuvering down Broadway, now a zigzag of a street, and my dad assumed the cabbie was lost, or worse yet, “taking us hostage.” I know this sounds horrible. My dad is not a horrible man, but in Alzheimer’s, I’ve found, paranoia often overtakes reality. Dad again began yelling swears at the driver. It got worse. He was out of his mind. Literally.

“Do you know where the (expletive) you’re going?” he screamed at the cabbie. “This is bullshit…Where the hell are you taking us? Pull over, dammit, just pull over now!”

In full rage, Dad bolted from the cab. I followed. The driver, sensing my father was in the throes of an emotional issue, tried to calm him down. It worked to some extent.

“What do I owe you?” Dad asked. The meter read $10.25.

“Nothing,” the cabbie replied. “You don’t owe me anything. I am sorry.”

The return from Pluto at times can be swift for my dad. Realizing he had been “out-of-body,” my father gave the driver a twenty-dollar bill. “I’m not a bad guy,” he told the cab driver. “I’m the one who needs to apologize here. I just have some issues. And I’m sorry.”

Dad then shook the stunned cabbie’s hand, gave him what he calls a “manly” hug, and the cabbie, probably wondering what the hell had just happened, drove off. Now we were standing on Broadway in a crush of rush hour humanity with our luggage and no ride. When I suggested that we call another cab or an Uber, Dad, who apparently had crash landed from Pluto, slipped into rage again, grabbed his oversized bag, handed me cash for a cab, then vanished into the masses.

“I’m done,” he said. “I’m done…”

Our family has learned that when Dad hurls into an Alzheimer’s rage to let out some rope, like the spool of a fishing rod. I couldn’t stop him, a hail of bullets couldn’t stop him, so with great reluctance I let him go. Except this time, Dad had cut the line. Seconds later, reality hit me: Oh my God, Dad is lost in New York, dragging a heavy oversized bag with a bewildered demeanor that says he’s bait. I was in a full-blown panic. The only saving grace was that he had the hotel address in his pocket.

Later Dad told me that he was in such a fury, hauling his heavy bag along Broadway, that he had hoped, actually prayed, to be accosted by a street gang so he could liberate his anger. He had even decided what to tell his imagined attackers:

“This is NOT going to be a good day for you!”

Dad said he practiced the line for several city blocks.

Greatly concerned, I immediately hailed a cab to the hotel and tried to call my father. He wouldn’t answer. The cabbie was an extremely friendly and engaging guy from Ireland. I don’t come across a lot of Irish cabbies in New York City. We talked. Instantly, I felt reassured. I thought it was a sign from God that Dad was OK. We spoke about our family trip to Ireland for Dad’s 60th birthday, about time spent in Dingle, Galway, and Ring of Kerry. I was at ease. Still my father wouldn’t accept a call. In angst again, I began thinking of Michael Scott, a.k.a. Steve Carrell, hopelessly lost in New York in an episode of The Office.

So I phoned my mother.

“You need to call Dad immediately,” I said. “He’s not answering his phone. Call him now, now, now!”

“Where is he?” she asked, building up to a panic herself.

“He’s lost on Broadway…”

“He’s WHAT?”

You can imagine the exchange from here.

So Mom started speed-dialing Dad, but still he wouldn’t answer. He was chumming for would-be attackers. Upon my arrival at the hotel lobby, I called him. He finally answered, then I saw him off in the distance towing his suitcase, like a bulky garbage bag, toward the hotel. He had stopped 15 strangers along the way to get directions, or maybe to pick a fight. I was awestruck.

At first, he refused to talk, but at least he was safe. Another close call. Dad is a survivor.

Not all episodes on the Pluto loop are so intensely charged. One time in Portland, Maine, after speaking before 500 people at an annual Alzheimer’s Association conference, my father removed himself from the auditorium to sit alone out in the lobby. He was spent, mentally exhausted, and wondering if anyone was listening. Dad doesn’t want pity; he just wants to offer encouragement and perseverance to others. When he looked up, there were more than a hundred people lined up to talk to him. Those in line didn’t want to talk about how Dad was feeling (they knew he wouldn’t go there); they wanted, instead, to talk about their families, their journeys. Dad lit up like a candle.

The effort he puts in each day of raising awareness of this disease is remarkable; his passion for those in the same boat is limitless. His words are powerful. Those who come to hear him seem to connect on a certain level with him regardless of whether they have or have not personally met him.

When Dad asks me to speak on the road, often I’m not sure what to say, so I speak from the heart, as he has taught me. I talk about the little things I notice now, such as the rage, confusion, and dislocation that he goes through daily, his day-to-day short-term memory problems, whether he’ll be asking where his keys are when they’re in his hand, reaching for his Big Bertha driver on the golf green, thinking it’s his putter, or calling out for our dog Sox before she died when Sox was sitting at his feet. I’m not sure mentally where Dad is at those times, but those blank stares are so peaceful. He’s calm, not stressed, and honestly seems not to have a care in the world. That’s the silver lining of this disease: learning to deal with it.

I can’t say enough about my father; he has qualities that people would die for. I would take a bullet for him; so would Brendan, Colleen, and my mother. Dad is not only fighting Alzheimer’s, but a long list of other serious medical issues. You’d never know it; he’s on a mission about this disease, and just busting his ass against all odds to make a living.

One of the hundreds of things I love about my dad is his sense of humor. He still has it, and I pray every day that he doesn’t lose it. He can take a joke like no one else. If you look in the dictionary for the meaning of self-deprecating humor, it will likely say: see also Greg O’Brien. Dad relishes the mockery. His humor, passion, and love for his family and friends is all he needs now. That’s not going anywhere for the moment, though the constant Alzheimer’s progressions we, as a family, will never fully understand. Dad won’t let us in. He is still the man of the family, whether he can act like it or not. Dad can go from complete rage, to laughing it up with family and friends in seconds. Seeing my dad smile warms my heart in so many ways. His sense of humor and a few laughs a day really help in fighting this disease. He takes pride every day in waking up and giving Alzheimer’s the finger.

You gotta laugh at life, the Irish way, Dad says, stare down the demons. We all need to do more of that: laugh, cry, think, love, and stare. My time with my father, and who he was, is now fleeting. I know that. Yet I know that the journey I’ve been on with him will sustain me forever. Through good times and bad, Dad is the same loving father, and he possesses a heartwarming soul that will never leave him.

Unforgettable

Brendan McGeorge O’Brien

Alzheimer’s is terrifying, but not because I fear the disease itself. Yet I know it could be my future. What I fear most is the menacing wake that Alzheimer’s leaves in its path. My father’s waning memory will one day erase his perception of who I am, who he is, and of every moment we’ve shared together. The word unforgettable has new meaning for me today. Unforgettable moments in life are truly rare, and in this certain fear, I’ve learned to cherish every single one of them. Never forget.

The awe of the Cape’s vast coastline falling into the wrath of a consuming sea is something my father taught me to never forget. The analogy is not lost on me now, as erosion of my father’s memory devours. The attrition of the high bluff above the Great Outer Beach was part of what Dad called our “backyard,” and as a first-born son, I was his sidekick in exploring its splendor. The bluff, my dad, continue to slowly slip.

On countless Saturdays, particularly when autumn had thinned the summer crowd, we would pack lunches and fishing rods and haul our canoe down to nearby Lower Mill Pond in Brewster. Barely old enough to bait a hook, I would laughably tell my mom, “We’re headed out to do what men do!”

Dad has always been my hero. My mentor. My best friend.

Almost 25,000 years ago, Lower Mill Pond was a lifeless crater, discarded from the clawing drag of the vast Laurentide Ice Sheet. The pond, long-sufferingly, had spent thousands of years transforming itself into a brilliant habitat, one of Cape Cod’s historic kettle ponds. In childhood it was a sanctuary to me, a place where I learned of nature’s unrelenting force and the marvel at its creation. My dad would always tell me, “It takes time, but nature always finds a way, day by day.”

Soon after my father’s diagnosis, I found myself just a few miles from that same pond, with power of attorney documents spread across our family oak living room table, wondering where I should sign. Dad had given me everything I ever needed in life, and now had to sign over whatever it was he had left. Wasn’t fair, and I wanted no part of it. For two Irish guys who didn’t like to talk about their emotions, we kept it business as usual, signing the documents, cracking a few jokes, and deciding it was time for a walk.

It had been close to twenty years since visiting the Mill Pond together, but without debate, we found ourselves at the head of the nature path we knew so well. Everything was just as I had remembered: the crowds were gone; the air was light; and winter was just a few storms away. Except this time, there was no canoe, no fishing rods, no packed lunches—just a deafening silence that stalked us.

Skirting the tip of a large granite boulder at the water’s edge, a remnant of the ice sheet, we sat side by side, blankly staring into the distance. Becoming his power of attorney had implications that neither of us wanted to acknowledge. The icy silence of the pond’s crater had returned; like a nuclear winter, it pulled us in, and defined the moment.

Tears began to stream down Dad’s face. “I’m so fucking scared,” he mustered, “I don’t know what’s happening to me.”

I’d never seen him cry. In that moment, I wanted to tell him everything would be okay. But I couldn’t. I knew it wouldn’t be okay. We buried our heads into the arms of one another, and tried to let it wash away. It was a far cry from early days on the pond “doing what men do,” as we let our fears cascade into the pond.

The torment of Alzheimer’s doesn’t start in a nursing home; far from it. Instead, it’s a tireless journey with no predictable direction, and it commences long before one is prepared to embark.

I spent most of my late-twenties growing impatient with my father. His once lovable “artistic quirkiness” had soured into a predictably stubborn, inflammatory character flaw, as I saw it then. As a family, we found it therapeutic to ignore the blatant warning signs of Alzheimer’s, not wanting to embrace our inevitable future.

I never expected to escape my thirties without some degree of loss, but Alzheimer’s has a perverse way of making one re-live that painful loss every single day, at a glacial speed, but knowing it will never retreat.

No one signs up for this. But the logical step is to forge on, start redefining the loss, and assess how the disease will impact the lives on the edge. Then comes the undeniable ethical dilemma: how much will we let this disease dictate our lives? What kinds of sacrifices will we make, and at what cost?

Whether we bear the disease like a cross, or wear it like a badge, there is peace in walking a chosen path with inherent decisions and inner conviction. Selfishly in the moment, I thought the diagnosis could not have come at a worse time in my life. I was just getting started with my writing and producing career, lots of dreams filled with promise, then the pink slip. Dad has Alzheimer’s! I, too, was feeling like George Bailey in It’s a Wonderful Life. I wanted out of the Bedford Falls of my past, but was getting sucked back in.

I found that reality has no regard for timelines. In my heart, I accepted that Alzheimer’s may one day define my own life, but that I would never let the disease dictate it. Though I don’t have the GPS coordinates for this disease, I’ve tried to guide my parents into uncharted financial waters. Financial planning, the gathering of family assets, and advising on long- and short-term options are just the beginning; nothing in life prepares us for the path ahead.

Dad says fighting Alzheimer’s is like a board surfer breaking the waves to paddle to the swell. The forces of nature keep crashing down. Dad’s first assault against this tide was making it to my sister Colleen’s wedding. Like so many families, it was a day we had all dreamt about. We were letting her go, like a firefly, to steady blinks of bright happiness with the kind of guy who would chase down her every dream.

But Alzheimer’s brutally exposes the significance of life’s precious milestones. Watching my dad’s father/daughter dance with Colleen was heart-wrenching. I found myself sobbing.

I’m engaged now to a beautiful woman, Laken Ferreria, the love of my life. I recently proposed to Laken on Martha’s Vineyard, at sunset on Menemsha Harbor. I pray my dad can toast us at our wedding. I find peace in knowing his legacy will never leave us. The inconsolable pain comes from knowing that the story of our lives together is drifting away. These unforgettable moments will one day be lost on him, and we’ll have to start over. Again, and again. It’s the painful reminder of that loss that hurts the most.

It took me a long time to take the leap outside of my own hurt. I had to abandon willfully my perception of reality. Alzheimer’s steals memory, family, and realities.

A close family friend and author of Still Alice, Lisa Genova put everything into perspective with one swift sentence. She told me, “If your dad thinks the sky is purple one day, just let it be purple.” It’s agonizing to think that he won’t know who I am someday, but there’s no solace or gain in frustration from that. He knows when he can’t remember something, and when that happens he just needs an embrace, not a harsh reminder of his disease.

This is a war we must all wage together, and the only way to win is to talk about it; take it public, and bring it out of the closet, as we did with cancer and AIDS. With close to 50 million affected across the world, proportionately more women and men, and more to come, we have power in numbers. Wear Alzheimer’s like a badge of honor, and make the disease regret the day it ever crossed your path. I’ve heard my dad’s close friend and best-selling writer David Shenk say of my father, “Alzheimer’s picked the wrong guy…”

Until local, state, and federal governments truly understand the disease, we’ll never get the funding to find a cure. Capitol Hill, on all sides of the political aisle, needs to continue to listen and to act. Alzheimer’s is a bipartisan killer. We will never fully, all of us, understand the disease until we collectively listen to the stories of the millions affected. It’s the truth, in our vulnerability, that will create real progress.

Our family journey has been filled with challenge, sadness, and fight, but it’s also been filled with opportunity—opportunity to share our story, your story, to strengthen relationships, and to cherish the time we spend together.

Breaking the icy silence that day at Mill Pond is what jumpstarted our family dialogue, and on our collective terms. The gaping crater the ice sheet left behind 25 millennia ago has slowly filled with beauty and life. We find peace in that.

My father may never be able to share the unforgettable moments of my future, but those whom I love will know of the hope he gave to others. That’s the legacy my children will someday know. Mom and Dad, I’ll always be right there with you guys, fighting dementia with all I have. Everything you’ve taught me will live far beyond our years, and I wouldn’t trade that for anything in the world. Our love is unforgettable. Here and on Pluto…

Walking in Faith

Colleen (O’Brien) Everett

“Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see.”

— Hebrews 11:1

Faith is a stretch at times. It is believing in something one cannot see, desperately reaching out at times into a void. Faith is the only thing stronger than fear.

My father has always been a man of faith. Some of my earliest memories of him are watching him kneel by his bedside with eyes closed, clutching a tattered Bible that was peppered with personal notes in his scratchy handwriting. A perfectly imperfect man, by his own admission, he would be so deep in thought and prayer that he would never even hear you enter the room. At the time, I was too young to understand the worries weighing on his heart, but I grew up learning that when life is difficult, or even when it is wonderful, or when one sins, as my father can with the best of them, one needs to close their eyes and talk to God.

Everything was less scary to me as a kid, and eventually as an adult, because I saw the power of faith through my father’s eyes: that no matter what life puts in front of you, God is already one step ahead of you. The Lord has a plan.

Well, I’m pissed off today about God’s plan for my dad. Yet, I try in faith to listen.

Looking back, I don’t ever remember my father yelling in torrents. He hardly ever lost his cool. When he coached my youth softball team, he would gently guide me to focus on fly balls, instead of picking dandelions in centerfield with my childhood friend Liz Seymour. Or when our team cheered wildly after a member of the opposing team hit a home run—anathema to my sports-minded father—he would just smile. Or when as young kids, Brendan, Conor, and I found ourselves on Saturday mornings, beyond stated boundaries, playing hide and seek by the printing press at the Cape Codder newspaper where Dad was editor and publisher, my father jokingly would get on the public address system and loudly announce: “Brendan, Colleen, and Conor, to the Principal’s Office! Brendan, Colleen, and Conor, to the Principal’s Office!!”

Later, when I began dating, Dad welcomed boyfriends into the house with a hug instead of an intimidating glare. My older brother, Brendan, often had to take on the responsibility of scaring off rogue teen suitors. Dad rarely swore in front of us then, and treated everyone with respect; he saw the good in everyone—no matter their story, their look, or their past. Still does. He has always been one to reach out in gut instinct to help and mentor those in need, usually outside of the view of others.

Today is a different narrative in our journey with Alzheimer’s. Now Dad has violent outbursts and eruptions of profanity. When he gets confused, which is often these days, he lashes out—usually at the people who love him the most. Outings with him can become uncomfortable, painful actually. At times, for example, I want to grab the waitress or cab driver, or whoever he’s yelling at, and let them know it’s not them, it’s not him. It’s Alzheimer’s.

A few years ago, my father was invited to speak in San Francisco. The trip happened to coincide with my spring break as a teacher in Baltimore City, so I agreed to go as his caretaker. He doesn’t travel alone. I remember my mother asking if I was sure I could handle it. Living now several hundred miles away from the Cape, I don’t get to witness the full picture of my father. When he only sees me for a short period of time, he is able to use up all of his energy to be in the present with me. I don’t always see the darker side of the disease that my mother and brothers do. Until I spent a week as his caregiver, I had no idea how much of my father this disease has consumed.

Going through airport security without a second thought, I took my shoes off, put my bags on the conveyor, and walked through the AIT machine. I then heard someone spewing profanity behind me, and my stomach dropped. My father couldn’t figure out how to take his belt off, and the TSA officer wouldn’t let him through until he did. In that moment, nothing made sense to my father. He knew that he should be able to take his own belt off, yet couldn’t. From 30 feet away, I had to watch the man who raised me to be a kind soul and taught me to field ground balls break down over his belt, as crowds of people stared in judgmental confusion over his confusion. In that moment, we switched roles. I became the parent. I closed my eyes, and asked the Lord for the strength to calm my dad. I made eye contact with him from the other side of the security screening, and coached him through the rest of the security line, like I would with one of my young students. I felt embarrassed and then immediately guilty for feeling that way. I knew that it was Alzheimer’s, not my father. But that’s the thing with Alzheimer’s; it strips the person you love of all elements that make them who they are. There are many things that define my father—he is a devoted husband, a loyal friend, a loving father, an avid sports fan, and stubborn Irish. Alzheimer’s does not define my father, but it does slowly strip away all of the things that do define him. All of the things that make him who he is.

My father today has become more childlike; the disease takes you there. And maybe that’s a good thing toward the end of one’s life. We all are so busy being adults that we forget the beauty and innocence of being a child, reinforced in me now as a young mother. Dad, in his disease, has found the balance sought in the Gospel of Matthew 18:2-4, “I tell you the truth. You must change and become like little children (in your hearts)…The greatest person in the Kingdom of Heaven is the person that makes himself humble as a child.”

Dad is now a child in so many ways.

Each Father’s Day, I can’t help but wonder how many more I’m going to have left with my dad. And not just physically, but mentally—where my dad remembers me, and remembers my daughter, Adeline. It’s a terrible thought, but one I can’t seem to get off my mind. Watching him slip away has been one of the most painful things I’ve ever had to experience.

While I can’t help these thoughts from flooding my mind, I also think of the wonderful memories that I do have: baseball games in the front yard; father/daughter trips to Fenway Park; ice cream at the Smuggler; and summer walks on the Brewster flats on the Cape. My father coached my little league softball team; as school committee chairman, gave the commencement speech at my high school graduation and handed me my diploma; surprised me with a yellow lab puppy for my 16th birthday; and walked me down the aisle on the most important day of my life. Alzheimer’s may take a lot from my family, but it will never take those memories away from me.

It’s really incredible to watch my father with my infant daughter. It’s a moment I wasn’t sure if I would ever get to have. I’ve read that children can reach those in the throes of Alzheimer’s at a deep emotional level—a level that most adults can’t. That’s the grace of being a child, for Adeline and for my dad. I’ve seen it in the way that Adeline looks at my dad. She looks past his temper and his confusion, and only looks at him with adoration and love. When she smiles, she smiles with her whole face. She can’t help but be all smiles when she’s with my father.

She is in awe of him, as I am, too.

My father today has a short commute to work. The path from our home’s back deck to his writing studio on the Outer Cape is lined with broken clam shells that mark the path like airport runway lights as he comes in for a safe landing. He can’t get lost there.

Halfway up the narrow path, at the base of an old oak tree, is a yellow Tonka toy truck, weathered with age. Conor and I used to play with it. The wheels, ironically, are now off; the plastic toy truck has been parked by the tree in solitude for close to 20 years. Dad put it there as a memory of our childhood, not far from what he calls “Christmas Tree Heaven,” a patch of woodland on our property piled with the bones of family Christmas trees from all these years of our childhood. My father is a sap, excuse the pun.

The yellow truck, angels, and the color yellow are driving forces in his life; they give my father great comfort. It brings him back in faith to an innocent time, to childhood, and to his own young fatherhood. On his way to the office, he religiously touches the top of the toy truck and says a prayer, as if to reassure himself that he has a past. We often quietly witness the exchange from behind the sliding door of the family room.

In Baltimore, which I now call home, my husband, Matt, and I discovered a little more than a year ago that “we” were pregnant. I was carrying the baby; and Matt was carrying me. I had always wanted to be a mom; it’s been something I’ve looked forward to my entire life. But as I sat on the floor with our new yellow baby lab, Crosby, awaiting the test results, a crushing feeling of anxiety swept over me: I was anxious about having to leave my six-year-old students a third of the way through the school year; I was anxious about being a good-enough mother; I was anxious about giving my students, my husband, my child, and our new puppy all of me. How does one even do that? I was far more fearful about passing the Alzheimer’s gene on to our child. I was scared that if I had the gene, like my dad, I’d leave my baby too soon.

I woke up early one Saturday morning a few weeks later, then almost 12 weeks pregnant, and decided to go for a run—a route I’ve been running since we moved to our neighborhood in Baltimore. There is a house on my route where three young kids live. They’re always outside playing with chalk or games in the yard, and when I’m running by or walking Crosby, they love to say hi. When I ran by the house early that morning, no one was awake yet, but something caught my eye. By the big tree on the front lawn was a yellow Tonka truck—just like the one we grew up with. I stopped, held my hand over it, and felt a rush of calm. Faith told me everything was going to be right in God’s plan.

This past Christmas Eve, I introduced my healthy baby girl, Adeline, to my father, a moment I never knew I would have. He held my angel tightly, and they danced slowly, grandfather to granddaughter. All was good in that moment. While we do not know what the future holds for all of us, I’ve come to understand that we can have faith in God’s plan. No matter what you choose to believe in, a personal choice for all, I’ve learned in this trial that one needs to have faith in something.

I have renewed faith today in angels, and in yellow Tonka trucks.

Caption: At a tavern on the Dingle Peninsula, west coast of Ireland, August 2010: (from left to right), author Greg O’Brien; daughter Colleen; wife Mary Catherine; son Conor; son Brendan.